Preface

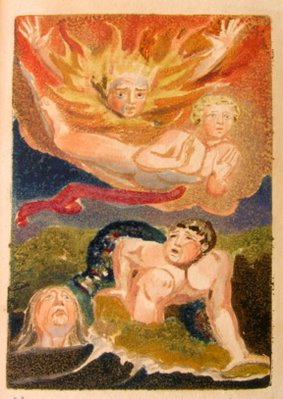

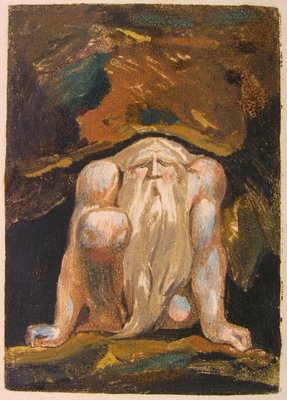

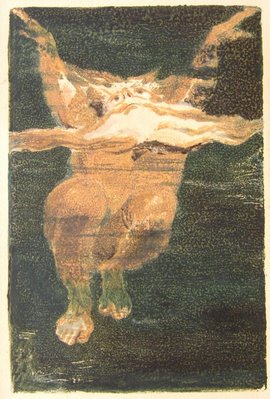

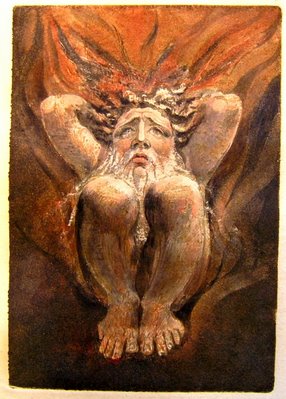

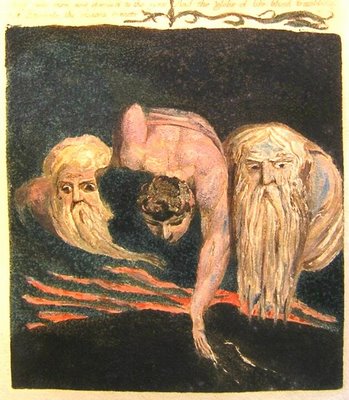

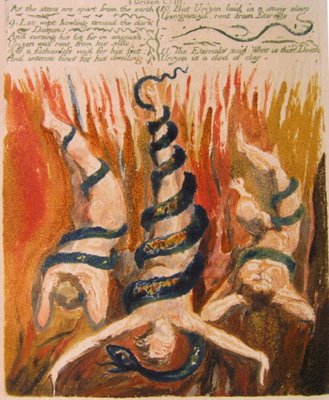

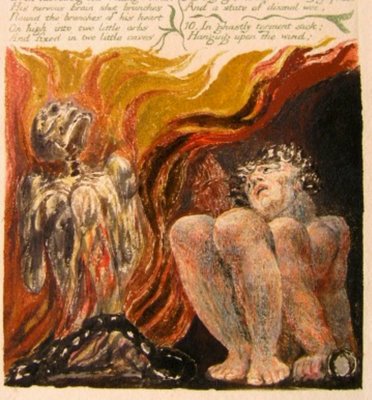

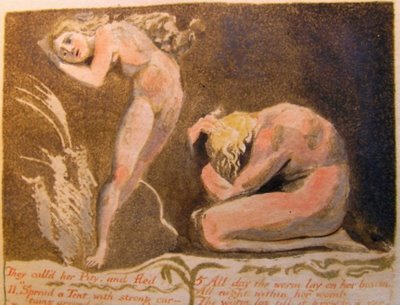

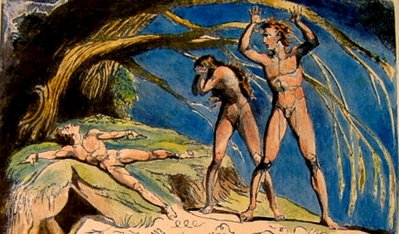

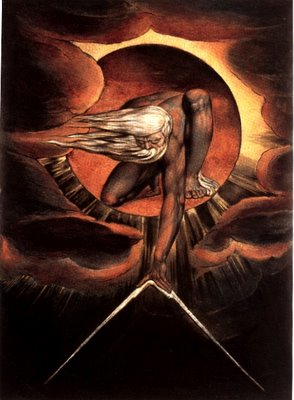

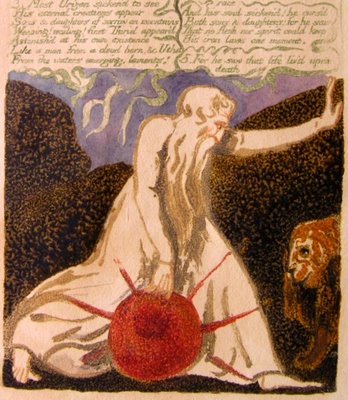

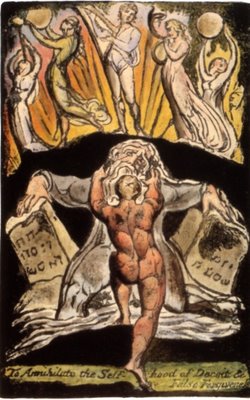

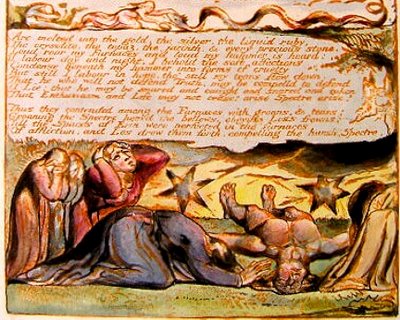

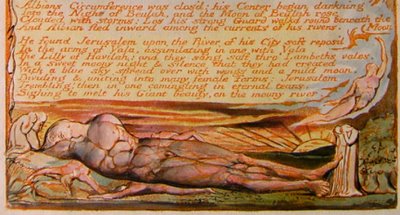

This blog, at "http://williamblakesspiritualjourney.blogspot.com," is a written version of a talk given for the Gnostic Church of Portland, Oregon, in the fall of 2005, and repeated for the Theosophical Society of Portland in February of 2007. The topic is William Blake's spiritual journey, as seen in the artwork of two of his illuminated books, The First Book of Urizen and Jerusalem, Emanation of the Giant Albion.

Initially I was more attracted by Blake's artwork than by the words that accompany them. In April of 2004 my wife and I had occasion to be in Connecticut, and we decided to visit Yale University's Beineke Library, which has originals of both these works. We spent one busy afternoon there, admiring and photographing these treasures.

As I looked at them at home, I wanted to know more about what they meant. So I got David Erdman's book The Illuminated Blake (1974); his understanding of Blake's images formed the basis for my talk at the Gnostic Church. In preparation for my second talk, I have read other interpretations and Blake's own words, which do not always clarify matters. I spent many hours sorting out those that I could actually see in the designs and fit to the text. I also read about his life. What I am presenting here is about 70% Erdman, 15% other interpretations, and 15% my own.

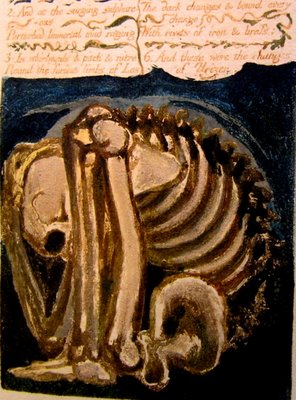

As a whole, the images tell a story, Blake's story of Urizen and Los, their exile from the eternals, their suffering in the fallen world, and their redemption in the New Jerusalem. It is also, as we shall see, the story of Blake's own unfolding awareness, full of despair, of his fallen state, and his overcoming of that state through art.

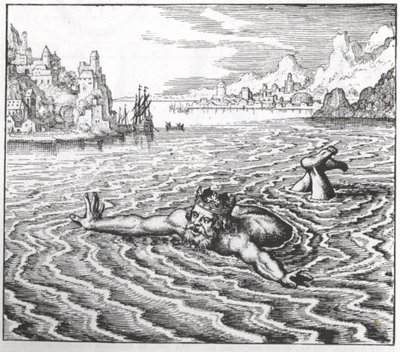

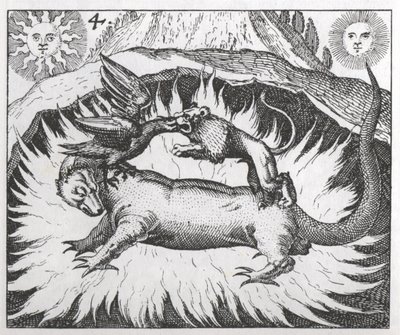

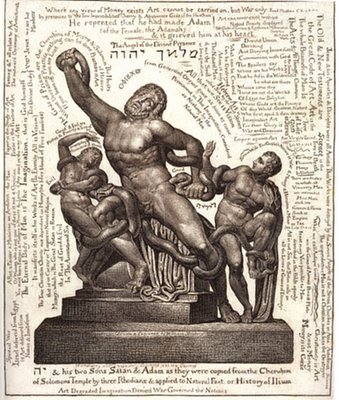

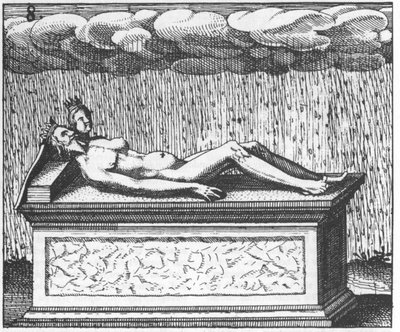

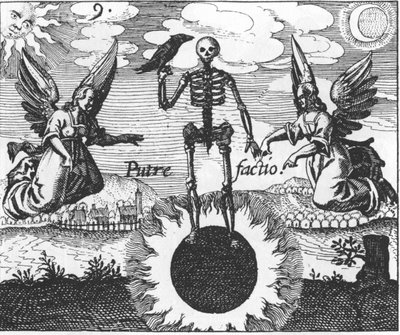

My own contributions, such as they are, are mainly in interpreting some of Blake's images by reference to alchemical images. I am not saying that Blake saw these images. He easily could have, because the books that contained them went through many editions during the previous century. But more importantly, they give us clues to how various specific images were used symbolically just prior to his time. My specific source for alchemical images is Alchemy: The Medieval Alchemists and their Royal Art, by Johannis Fabricius (1976).

After I presented the slide show to the Theosophical Society, one of its members, Tamara Gerard, went looking for where these images might be available in print. She found them in William Blake: The Complete Illuminated Books, edited by David Bindman. Indeed, the plates of Jerusalem are there in fairly good reproductions, although smaller in size and occasionally a bit greenish compared to the originals. (The ones here, by the same token, I sometimes made over-bright.). The images from Urizen are also good but from a different copy; so there are slight variations.

What disapponted me in Bindman's book were his images of the other illuminated works done around the same time as Urizen. Following the Blake Trust volumes he is drawing on, he uses images from British libraries that sometimes seem to me decidedly inferior artistically to the versions at Yale. For example, I never understood why critics found Blake's ill;ustration of "The Tyger" disappointing until I saw the image in Bindman's book, so anemic-looking compared to the one at Yale. So I decided to add two chapters at the end with the Yale versions that we photographed of this other work: The Book of Thel, America a Prophecy (which in Bindman isn't even colored!), and Songs of Experience. Yale has more, but we didn't photograph them. As I have done for Urizen and Jerusalem, I include enlargements of the illuminations themselves. Songs of Experience is Chapter 9, and the others are at the end of Chapter 8.

I will end this Preface by giving a few tips for navigating this blog. As you read down, those images that are wider than they are tall can be made larger by clicking on them. Then to get back to the text you were reading, use your back browser (the arrow at the top left of your screen). Wait a couple of seconds and the program will reload the text and return you to where you left off.

To read a specific chapter, you can click on the title of the chapter, at the right of this Preface. That will also shorten the reloading time when you want to return from an image to the text, if you are experiencing a delay. Then when you finish the chapter, you can either click on a new chapter title, to the right at the top of the chapter, or on "home" at the end.

Initially I was more attracted by Blake's artwork than by the words that accompany them. In April of 2004 my wife and I had occasion to be in Connecticut, and we decided to visit Yale University's Beineke Library, which has originals of both these works. We spent one busy afternoon there, admiring and photographing these treasures.

As I looked at them at home, I wanted to know more about what they meant. So I got David Erdman's book The Illuminated Blake (1974); his understanding of Blake's images formed the basis for my talk at the Gnostic Church. In preparation for my second talk, I have read other interpretations and Blake's own words, which do not always clarify matters. I spent many hours sorting out those that I could actually see in the designs and fit to the text. I also read about his life. What I am presenting here is about 70% Erdman, 15% other interpretations, and 15% my own.

As a whole, the images tell a story, Blake's story of Urizen and Los, their exile from the eternals, their suffering in the fallen world, and their redemption in the New Jerusalem. It is also, as we shall see, the story of Blake's own unfolding awareness, full of despair, of his fallen state, and his overcoming of that state through art.

My own contributions, such as they are, are mainly in interpreting some of Blake's images by reference to alchemical images. I am not saying that Blake saw these images. He easily could have, because the books that contained them went through many editions during the previous century. But more importantly, they give us clues to how various specific images were used symbolically just prior to his time. My specific source for alchemical images is Alchemy: The Medieval Alchemists and their Royal Art, by Johannis Fabricius (1976).

After I presented the slide show to the Theosophical Society, one of its members, Tamara Gerard, went looking for where these images might be available in print. She found them in William Blake: The Complete Illuminated Books, edited by David Bindman. Indeed, the plates of Jerusalem are there in fairly good reproductions, although smaller in size and occasionally a bit greenish compared to the originals. (The ones here, by the same token, I sometimes made over-bright.). The images from Urizen are also good but from a different copy; so there are slight variations.

What disapponted me in Bindman's book were his images of the other illuminated works done around the same time as Urizen. Following the Blake Trust volumes he is drawing on, he uses images from British libraries that sometimes seem to me decidedly inferior artistically to the versions at Yale. For example, I never understood why critics found Blake's ill;ustration of "The Tyger" disappointing until I saw the image in Bindman's book, so anemic-looking compared to the one at Yale. So I decided to add two chapters at the end with the Yale versions that we photographed of this other work: The Book of Thel, America a Prophecy (which in Bindman isn't even colored!), and Songs of Experience. Yale has more, but we didn't photograph them. As I have done for Urizen and Jerusalem, I include enlargements of the illuminations themselves. Songs of Experience is Chapter 9, and the others are at the end of Chapter 8.

I will end this Preface by giving a few tips for navigating this blog. As you read down, those images that are wider than they are tall can be made larger by clicking on them. Then to get back to the text you were reading, use your back browser (the arrow at the top left of your screen). Wait a couple of seconds and the program will reload the text and return you to where you left off.

To read a specific chapter, you can click on the title of the chapter, at the right of this Preface. That will also shorten the reloading time when you want to return from an image to the text, if you are experiencing a delay. Then when you finish the chapter, you can either click on a new chapter title, to the right at the top of the chapter, or on "home" at the end.