Chapter 3: Milton, Albion, and Jerusalem

After setting down his myth describing the formation of the world, Blake's version of Genesis, he devoted several of his visionary books to the problem of how to set things right. A few were about child Orc, who grows up to be a failed revolutionary. Another book, his rewriting of Exodus, imagined Urizen's son Fuzon and his followers leaving Urizen's domain, along with the feminine emanation Ahaina. All of these were engraved in the mid-1790's. Blake was now about 38 years of age, in his middle years

After that Blake published no more prophetic books for almost 10 years. He earned his livelihood illustrating other people's poems. Like his creation Urizen, he was caught in a web of his own making. On the side, he worked on an ambitious project called "The Four Zoas" that he eventually abandoned and never engraved. From 1800 through 1803 he spent three years outside London in the coastal village of Felpham, so as to be near his admirer Hayley. Hayley proposed that Blake do portrait miniaturues and thereby make a lot of money. But Blake did not only fail to make money, he also seems to have found the task quite painful. Meanwhile he worked on revising his "Four Zoas" yet again. By 1802 he felt he could write to his lifelong supporter Thomas Butts, "Tho' I have been unhappy, I am so no longer. I am again Emerged into the light of day...I have travel'd thro' Perils & Darkness not unlike a Champion. I have Conquered, and shall Go on Conquering. Nothing can withstand the fury of my Course among the Stars of God and the Abysses of the Accuser..." (Frye, p. 417).

In July of 1803, Blake wrote that he would have left Felpham after a month, had his "Spiritual Friends"--meaning, I think--friends in the spirit world--not advised him to stick it out. But, he said, his "three years' trouble Ends in Good Luck," because he completed what he considered "the Grandest Poem that this World Contains." It is an example of "Allegory addressed to the Intellectual powers, while it is altogether hidden from Corporeal Understanding." It will be "progressively Printed & Ornamented with Prints & Given to the Public." What he wrote in Felpham is now lost. What we have is his next revisions, known to the world as Milton, published in 1804, and the 100 plates Jerusalem, which finally saw the light of day in 1818-1820.. Even then, he did only one edition in color, and no one ever bought it in his lifetime.

In Milton, Blake summoned up the spirit of John Milton, the poet before him that he most admired, purged of his shortcomings and returning to Earth as Los confronting as Urizen. I have no photographs of Milton, but I do want to show you two images, which I have taken from published sources.

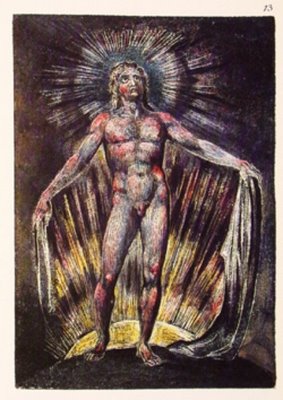

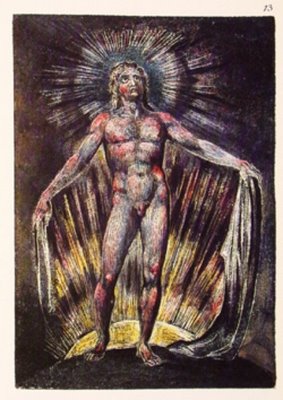

One memorable page (Plate 16) shows Milton as he "took off the robe of the promise, & ungirded himself from the oath of God" (15:13):

By "the promise" Blake meant any"covenant" between God and his people interpreted in a this-worldly way, that is, of the form, if you worship me faithfully, I will reward you in material ways-- money, love, prestige, etc. Such a contract simply bound one to a world of illusion.

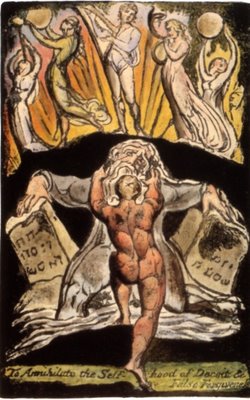

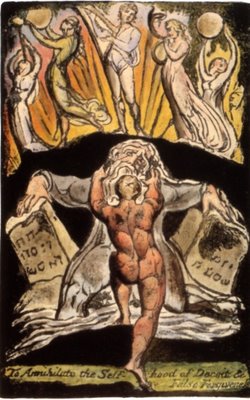

Having cast the world aside, Milton is in a position to take on Urizen. He separates Urizen from his tablets of the law and pushes him into the water. It is an ironic baptism in the river Jordan (Plate 18):

The words at the bottom read, "To annihilate the Self-hood of Deceit and False Forgiveness." He could perhaps have let Urizen drown. But Urizen has a way of surviving despite everything. Los here is both pushing him and also holding him from sinking. Urizen can be enlightened. It is not clear why the people on top are dancing around. Some interpreters have said that they are trying to entice Los into crossing the Jordan and into more illusion. Others say they are celebrating Los's victory.

Blake does not in this work follow through his grand design. In fact, I think there is something left out. It is not so easy to rid oneself of illusion and rise above the Law. It is like waking oneself up in a dream; one may only dream one is awakening. To reject the Law is not yet to live in freedom.

What does Blake have when his alter ego Los breaks the tablets of the law? On the title page of Urizen, Urizen wrote from two sides, Word and Nature. Urizen chose the Word, twisting it to his purpose as the vehicle of the Law. But the other choice, Nature, is equally twisted, since it has been copied out for us by Urizen. We experience nature, and Blake is concerned mainly with our own nature, through our "reasoning power." By such means love engenders jealousy and exploitation, merit produces envy, achievement becomes pride, reward turns into avarice, and so on. We have eaten of the tree of good and evil, and we are not in Paradise.

It is with such a realization, I think, that Blake started his masterwork, Jerusalem, Emanation of the Giant Albion, a book in 100 plates of words and images.

The Frontispiece (Plate 1) indicates where Blake is going. It shows a man with a lantern, probably Los, stepping across a threshold that appears to lead downwards, as though into the crypt of a church.

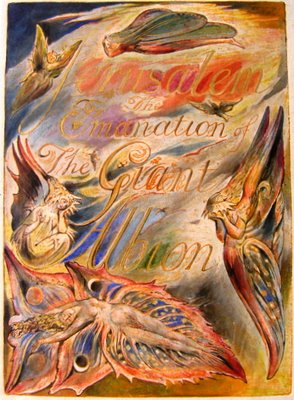

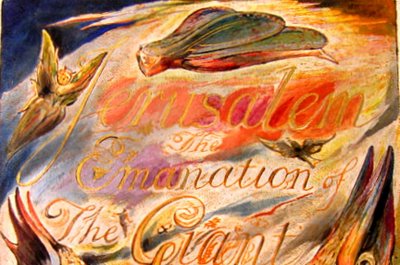

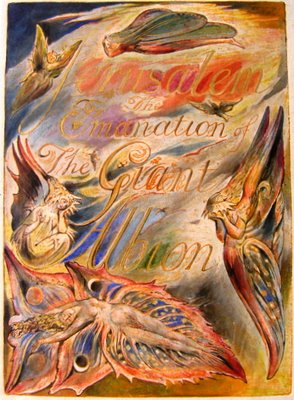

Next let us turn to the title page, Jerusalem, Emanation of the Giant Albion (Plate 2):

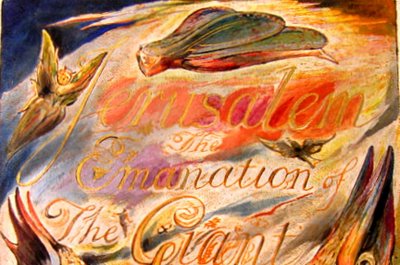

Albion is Blake's version of fallen Adam, particularized to Britain, which I think includes England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. He is the spirit of the British Isles in the fallen state. The images here give us one frequent metaphor for that state: being in a state of sleep or unconsciousness. It shows a sleeping Jerusalem, while her daughters flit over her and weep. Here are close-ups of the top and bottom of the page, the top showing the daughters and the bottom, Jerusalem:

And who is this Jerusalem, Blake's heroine? We are told only that she is Albion's "emanation." One possibility is that she is his wife, as Eve came out of Adam or Wisdom, Hochma, came out of the mouth of Jehovah. In Milton Jerusalem was the bride of Albion. Here, however, Jerusalem says that "the Lamb of God" made her "His Bride & Wife" and gave Vala to Albion (Frye p. 272). At least for now, Jerusalem is Albion's daughter. This multiplicity and switching of roles occurs in the Gnostic writings about Sophia, too.

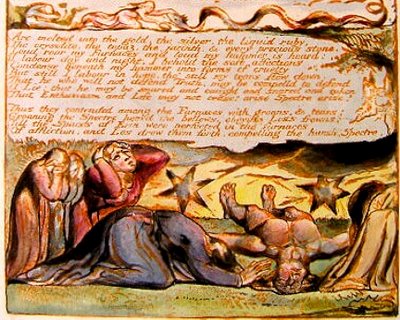

Albion slumbers, too, and is taken for dead, as the daughters of Jerusalem weep over him (Plate 9):

Blake presents Albion's condition here as a result of a fall from innocence. At the top of the page, shepherds pipe and pray.surrounded by docile sheep. That is the state of innocence.

Then comes the serpent and its forbidden fruit, and finally Albion's lifeless form at the bottom of the page..

As the drama unfolds, however, we shall see that Blake's view of the fall is not in fact a conventional one. Bit by bit we will learn more about what caused Albion's demise.

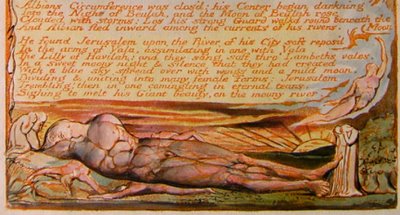

His sons and daughers weep over him. Here is another view, this time as a giant, like the Cabbalists' Adam Kadmon. Blake says, "But when they saw Albion fall'n upon mild Lambeths vale: /Astonished! Terrified! they hover'd over his Giant limbs" (20:1-2; Plate 19):

As for Los, he either dreams or has visions of "the mild Emanation Jerusalem," as I think the etching below illustrates (Plate 14). Erdmann says it is Albion in this picture, but the text only mentions Los.

After that Blake published no more prophetic books for almost 10 years. He earned his livelihood illustrating other people's poems. Like his creation Urizen, he was caught in a web of his own making. On the side, he worked on an ambitious project called "The Four Zoas" that he eventually abandoned and never engraved. From 1800 through 1803 he spent three years outside London in the coastal village of Felpham, so as to be near his admirer Hayley. Hayley proposed that Blake do portrait miniaturues and thereby make a lot of money. But Blake did not only fail to make money, he also seems to have found the task quite painful. Meanwhile he worked on revising his "Four Zoas" yet again. By 1802 he felt he could write to his lifelong supporter Thomas Butts, "Tho' I have been unhappy, I am so no longer. I am again Emerged into the light of day...I have travel'd thro' Perils & Darkness not unlike a Champion. I have Conquered, and shall Go on Conquering. Nothing can withstand the fury of my Course among the Stars of God and the Abysses of the Accuser..." (Frye, p. 417).

In July of 1803, Blake wrote that he would have left Felpham after a month, had his "Spiritual Friends"--meaning, I think--friends in the spirit world--not advised him to stick it out. But, he said, his "three years' trouble Ends in Good Luck," because he completed what he considered "the Grandest Poem that this World Contains." It is an example of "Allegory addressed to the Intellectual powers, while it is altogether hidden from Corporeal Understanding." It will be "progressively Printed & Ornamented with Prints & Given to the Public." What he wrote in Felpham is now lost. What we have is his next revisions, known to the world as Milton, published in 1804, and the 100 plates Jerusalem, which finally saw the light of day in 1818-1820.. Even then, he did only one edition in color, and no one ever bought it in his lifetime.

In Milton, Blake summoned up the spirit of John Milton, the poet before him that he most admired, purged of his shortcomings and returning to Earth as Los confronting as Urizen. I have no photographs of Milton, but I do want to show you two images, which I have taken from published sources.

One memorable page (Plate 16) shows Milton as he "took off the robe of the promise, & ungirded himself from the oath of God" (15:13):

By "the promise" Blake meant any"covenant" between God and his people interpreted in a this-worldly way, that is, of the form, if you worship me faithfully, I will reward you in material ways-- money, love, prestige, etc. Such a contract simply bound one to a world of illusion.

Having cast the world aside, Milton is in a position to take on Urizen. He separates Urizen from his tablets of the law and pushes him into the water. It is an ironic baptism in the river Jordan (Plate 18):

The words at the bottom read, "To annihilate the Self-hood of Deceit and False Forgiveness." He could perhaps have let Urizen drown. But Urizen has a way of surviving despite everything. Los here is both pushing him and also holding him from sinking. Urizen can be enlightened. It is not clear why the people on top are dancing around. Some interpreters have said that they are trying to entice Los into crossing the Jordan and into more illusion. Others say they are celebrating Los's victory.

Blake does not in this work follow through his grand design. In fact, I think there is something left out. It is not so easy to rid oneself of illusion and rise above the Law. It is like waking oneself up in a dream; one may only dream one is awakening. To reject the Law is not yet to live in freedom.

What does Blake have when his alter ego Los breaks the tablets of the law? On the title page of Urizen, Urizen wrote from two sides, Word and Nature. Urizen chose the Word, twisting it to his purpose as the vehicle of the Law. But the other choice, Nature, is equally twisted, since it has been copied out for us by Urizen. We experience nature, and Blake is concerned mainly with our own nature, through our "reasoning power." By such means love engenders jealousy and exploitation, merit produces envy, achievement becomes pride, reward turns into avarice, and so on. We have eaten of the tree of good and evil, and we are not in Paradise.

It is with such a realization, I think, that Blake started his masterwork, Jerusalem, Emanation of the Giant Albion, a book in 100 plates of words and images.

The Frontispiece (Plate 1) indicates where Blake is going. It shows a man with a lantern, probably Los, stepping across a threshold that appears to lead downwards, as though into the crypt of a church.

Next let us turn to the title page, Jerusalem, Emanation of the Giant Albion (Plate 2):

Albion is Blake's version of fallen Adam, particularized to Britain, which I think includes England, Wales, Scotland, and Ireland. He is the spirit of the British Isles in the fallen state. The images here give us one frequent metaphor for that state: being in a state of sleep or unconsciousness. It shows a sleeping Jerusalem, while her daughters flit over her and weep. Here are close-ups of the top and bottom of the page, the top showing the daughters and the bottom, Jerusalem:

And who is this Jerusalem, Blake's heroine? We are told only that she is Albion's "emanation." One possibility is that she is his wife, as Eve came out of Adam or Wisdom, Hochma, came out of the mouth of Jehovah. In Milton Jerusalem was the bride of Albion. Here, however, Jerusalem says that "the Lamb of God" made her "His Bride & Wife" and gave Vala to Albion (Frye p. 272). At least for now, Jerusalem is Albion's daughter. This multiplicity and switching of roles occurs in the Gnostic writings about Sophia, too.

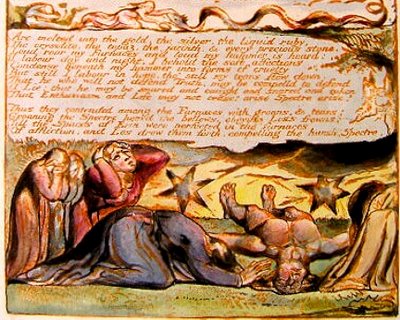

Albion slumbers, too, and is taken for dead, as the daughters of Jerusalem weep over him (Plate 9):

Blake presents Albion's condition here as a result of a fall from innocence. At the top of the page, shepherds pipe and pray.surrounded by docile sheep. That is the state of innocence.

Then comes the serpent and its forbidden fruit, and finally Albion's lifeless form at the bottom of the page..

As the drama unfolds, however, we shall see that Blake's view of the fall is not in fact a conventional one. Bit by bit we will learn more about what caused Albion's demise.

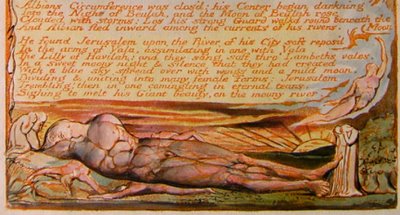

His sons and daughers weep over him. Here is another view, this time as a giant, like the Cabbalists' Adam Kadmon. Blake says, "But when they saw Albion fall'n upon mild Lambeths vale: /Astonished! Terrified! they hover'd over his Giant limbs" (20:1-2; Plate 19):

As for Los, he either dreams or has visions of "the mild Emanation Jerusalem," as I think the etching below illustrates (Plate 14). Erdmann says it is Albion in this picture, but the text only mentions Los.

1 Comments:

Amazing collection of William Blake Paintings.Thanks for sharing.

Post a Comment

<< Home